I wrote this post with my thoughts on the whole Franklin India debt schemes fiasco. But since then, there’s been more action in debt funds. I still can’t get over the fact that these damn things are supposed to be boring. Debt is supposed to the thing that allows you to sleep at night peacefully, not give you sleepless nightmares. But, all of a sudden investors are freaked out and rightfully so.

I’ve received numerous queries about whether they should sell their liquid funds and move to gilt funds, if their ETF investments are safe, what happens if an AMC goes bust, safe debt fund recommendations, and I am not even a bloody advisor – I make silly jokes on twitter like this one:

I can only imagine the number of queries advisors, distributors, and AMCs must be fielding. Before you go overboard giving investors credit for being vigilant, don’t you worry for even a second. This is just a temporary phenomenon, and if the markets recover, they’ll go back their usual selves of doing dumb things, but for the moment investors are freaked out.

All the news headlines that are trickling out post the Franklin event aren’t helping either. On Saturday, Principal India decided to write-off it’s DHFL exposure which saw few of its debt schemes falling 4-6% – nearly 1-year of returns wiped out in a single day. As the saying goes – debt funds are better than FDs!

But the reason I wanted to write this post is because there’s been some phenomenal writing on the various aspects of debt funds and the India debt markets at large post the Franklin fiasco. Given that on any given day there’s a fire-hose of information, chances are these pieces might get lost. So this post serves the dual purposes of helping me think about these things and as I write and as bookmarks if you are unfortunate enough to be interested in the debt markets like I am. Mind you, I might get a lot of things wrong and if you find some mistake, that’ll help me learn. That’s one of the advantages of publicly writing 🙂

Some rants, before some thoughts

Should AMCs make a more honest effort to disclose their processes and philosophies? This is a staple dialogue in all AMC communication – don’t choose a fund based on past performance but rather based on the process and philosophy. But how do you go about finding it? If I visit the website of ICICI Pru, it’s like browsing Amazon, it’s a bloody supermarket. It’s next to impossible to figure out their so-called processes and philosophies. It’s the same with most other websites barring a few smaller AMCs. One of the cooler and useful things I have seen over the past few years is that DSP MF started publishing detailed investment frameworks of their funds. Ironically, I don’t know why they decided to publish it as a PDF which is terribly undiscoverable rather than publishing it on the web. For equities at least, with some difficulty, you can kinda sorta figure out what an AMC does, how they pick stocks, etc by piecing various things together, but debt I’ve yet to come across a single AMC that has coherently managed to communicate its credit evaluation process. Every AMC says they invest in quality debt until you wake up to discover that your debt fund just lost 1 year’s return in a single day.

I was having a discussion about this couple of days ago and seemed worth highlighting here. Should AMCs do a better job of communicating whatever it is that they do and how they do it? Hell, yes! Transparency is always good, and it will make life easier for investors who actually make an effort to analyze and look at things closely before they make an investment decision. Will AMCs do it? I mean, nobody has made an effort to make life easier for investors in a decade and I don’t think they will. I have a feeling that AMCs build and maintain terrible websites and communicate in horrible ways to confuse investors so that the AUM flows in because investors are bound to say fuck it and invest in random funds.

But assuming that AMCs clearly communicated how they evaluate debt, internal structures, etc, would it make a difference? I am an eternal optimist in the belief that a vast number of dumb investors who refuse to make an effort to learn will far outweigh the sensible investing crowd by order of magnitude. But, at the same time, anybody that acts or is perceived to be acting as a fiduciary needs to make every effort to be transparent. But I am confident that nothing is going to change post-Franklin – there are no incentives powerful enough that can force change. The status quo is quite profitable!

The open ended mutual fund structure

Gallons of ink have been spilt on what happened with Franklin schemes, were the fund managers right, was Franklin right, and so on. But surprisingly, there has been very little discussion on the mutual fund structure itself. In this piece – first of a three-part series, Rajiv Shastri tackles that very question. Think about it, the open-ended mutual fund wrapper is more liquid than the underlying bond market. A mutual fund promises continuous purchase and redemptions every day even when the underlying bonds themselves might not have traded, in some cases for weeks. This means that when there is a serious liquidity shock like the current Corona Virus induced one, open-ended debt funds cannot sustain serious outflows for long. The reason being, when a debt mutual fund has net redemptions it sells off the easier to sell liquid bonds. If the redemptions intensify, it’s left with less liquid bonds, as it happened with Franklin and previously in DHFL MF (now Pramerica) schemes.

But it can also be said that debt mutual funds provide liquidity in the debt markets right? Then what’s the problem, which is what I asked Rajiv on twitter. Hot and impatient money being accommodated in a liquid wrapper on top of an illiquid market might be the problem.

This is why plenty of knowledgable people were of the opinion that an alternative investment fund (AIF – the Indian equivalent of a hedge fund) might be a better structure to run high yield credit funds because AIFs often have lock-ins which take care of the sudden redemptions problem.

This also leads to another interesting discussion on NAVs itself. In an equity scheme, there’s an active underlying market that prices stocks continuously and at any given point you know the exact value of the underlying basket of stocks in a mutual fund. But it’s different in a debt mutual fund. Expect for G-secs and AAA-rated bonds, most other bonds trade sparingly. Which means some of the lesser rated debt can go on untraded for weeks and months. If a mutual fund is holding them and has to declare a NAV how does it do it? It sources pricing for these bonds from valuation agencies like CRISIL, etc. How do they value bonds? The details of models aren’t fully public, but it can be based on various things like last traded data, asking bond dealers, etc.

But at the end of the day, it’s extremely hard to accurately value these papers. The valuation agency might come up with a number that might be totally different from what the market participants think. This means the NAVs of debt mutual funds is partly fiction. Let’s say XYZ debt fund has a NAV of Rs 10 and an AUM of Rs 100 crores and let’s assume that it has Rs 30 crores of super liquid bonds that are decently traded. Assuming that it gets Rs 28 crores of sudden redemptions, it can sell the liquid bonds and meet return the money to investors at the Rs 10 NAV. But it gets tricky after if it gets Rs 20 more cores of redemptions, and the rest of the bonds it holds don’t trade much. The price at which it can sell the remaining bonds will be way different than the NAV which is based on the pricing of a model.

In times of severe redemptions, the NAV is pretty much applicable to the smart guys who get out first. Post that, it’s a distress sale and NAV and actual market prices of bonds can be wildly different.

Today, assuming that Franklin India tries to get rid of the bonds in the 6 schemes that it’s shutting down, the price they’ll receive for the bonds will way different than the prices determined by the bond models. Which brings me to this really good piece by Prof Hemant Manuj. Here’s an excerpt from his piece:

It is a cardinal principle of regulation in the area of financial markets that those holding fiduciary responsibility must disclose to the stakeholders all material risks known to them. The lack of accurate valuation of bonds is a material risk, and one that should be well understood by the funds. In such a scenario, the AMC should is expected to make periodic disclosures and take other related steps to mitigate the risk of imperfect valuation of illiquid securities.

The ratings issued by credit rating agencies are merely their opinion, and yet, their methodology and outcomes are overly regulated. However, the methodology for valuation of illiquid securities is neither available for discussion nor is appropriately regulated.

Livemint

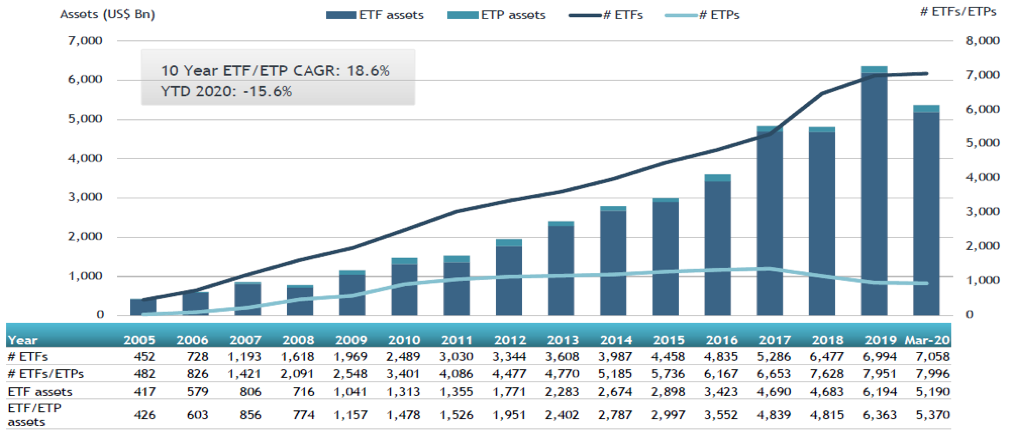

Which brings us to the next question. If debt mutual fund NAVs can be inaccurate, is there an alternative? Yes, ETFs. In the past couple of decades, very few financial innovations come close to being as impactful as exchange traded funds. They’ve democratized low-cost access to stocks, bonds, commodities, real estate, and even hedge funds like alternatives.

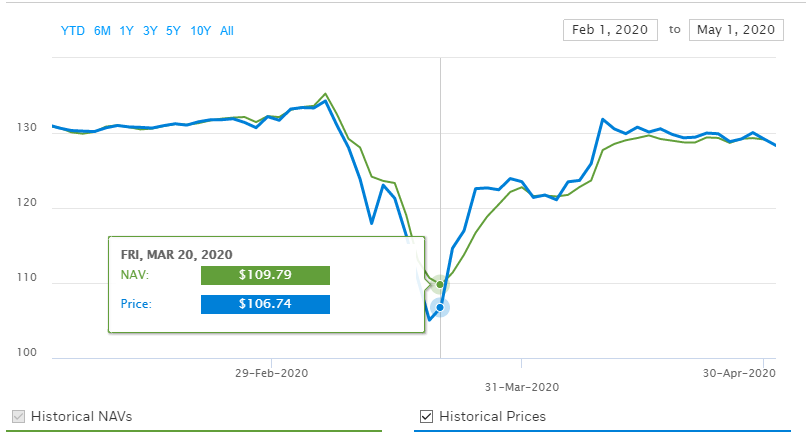

Anyways, bond ETFs also have vilified for a long time with the same refrain that they will exacerbate risks in the bond markets given that ETFs provide ready liquidity in an asset class and market that is highly illiquid. Everybody from Howard Markes to El Erian have expressed concerns. The Corona crisis was a perfect test for bond ETFs, there were severe dislocations even in US treasuries which is the world’s most liquid and traded fixed-income security. But all things considered, ETFs have performed admirably. But given the insane and mindnumbing volatility, several of the biggest bond ETFs started trading far away from their NAVs. Hold on let me finish before you kill me pointing to the fact that I just said ETFs performed well and now I am saying that some ETFs traded away from their NAVs.

Here are the charts of The Vanguard Total Bond Market (BND) and Mutual Fund (VBMFX) and the iShares Investment Grade Corporate Bond ETF (LQD). I couldn’t pull a chart of the ETF price vs the NAV for BND, but it’s still the same thing because these funds are the exact same. For some context, BND has $51billion in AUM with an average daily traded volume of $650 million. LQD has $46 billion in AUM and an average daily traded volume of $2.7 billion. There are the most liquid ETFs out there.

Notice the sharp disconnect between March 12-20th? The ETF was trading at a lower price than the ETF. Does that mean the NAV is more accurate than the real-time price of the ETF? No, this comes back to the same debate about how bonds don’t trade much and that NAVs are based on prices from valuation agencies.

Now, in the case of an ETF, it trades throughout the day like a stock and there is real-time pricing. One key thing that distinguishes ETFs from MFs is that ETFs have market makers. The job of the market makers is to provide liquidity. Also, whenever there’s a disconnect between the NAV and price of an ETF, the market makers step in to arbitrage the price, I won’t get into the details, you can check out this Indexheads post if you want to learn more about market makers.

Anyway, this phase of the market volatility seems to have shown that the price of an ETF is a better signal of the true value of all the underlying bonds of the ETF than the NAV – which is model dependent. Why? Because the price of an ETF is real-time and it shows the collective judgment of the market of the value of the underlying bonds in an ETF. If the market makers didn’t step in, that means they figured that, that the NAV doesn’t reflect the true value of the underlying shares and the value of bonds is probably in line with the ETF. An excerpt from this brilliant piece by Dave Nadig, probably the foremost expert on all things ETFs on planet earth:

Put another way, to make money off this gap, an Authorized Participant has to go out into the market and buy a pile of shares of the ETF, while simultaneously selling all the bonds it knows it will take delivery of when they hand their collection of BND shares into Vanguard for a redemption. That would let them “sell high” (selling the bonds) and “buy low” (scooping up those ‘cheap’ ETF shares.)

But they didn’t So we can conclude that nobody in the market believes they can make that trade work. They know that when they have to SELL the bonds, they’ll get prices that are much more in line with the price activity in the ETF than the magical Net Asset Value line that would imply a profit.

ETF Trends

Even the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) in a recent bulletin came to the same conclusion:

In mid-March, the prices of many corporate-bond ETFs dropped noticeably below the values of their portfolios (net asset values (NAVs)). These NAV discounts reflected several factors. First, in the light of the relative illiquidity of corporate bond markets, NAVs incorporate information more slowly than prices. As a result, deviations are more likely to open at times of volatile markets. Second, dealers provided less support to corporate bond liquidity, potentially limiting the arbitraging of NAV discounts. Third, flows to money market funds (MMFs) accelerated after US federal banking regulators announced the MoneyMarket Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (MMLF). Contemporaneous outflows from investment grade (IG) mutual funds rose abruptly, pointing to a possible rebalancing from short-duration IG ETFs to MMFs.

BIS

Several lessons can be drawn from these events. In particular, policy interventions in one market sector can have significant, if temporary, impacts on related segments – even as market functioning improves –when investors rapidly adjust their portfolios. In addition, ETF prices are more reactive to market developments than the prices of the underlying bonds are, especially at times of market stress. As such, ETF prices are probably more suitable inputs to monitoring efforts and to risk management models, including those underpinning regulatory capital calculations, than relatively stale bond benchmarks.

In India, these are very early days for bond ETFs. We’ve had GILT ETFs for a long time but all put together they hardly have a few crores in AUM. There are probably 7 people who even know that these GILT ETFs exist. But Edelweiss last year launched Bharat Bond ETF – India’s first corporate bond ETF and I’m a fan of the product.

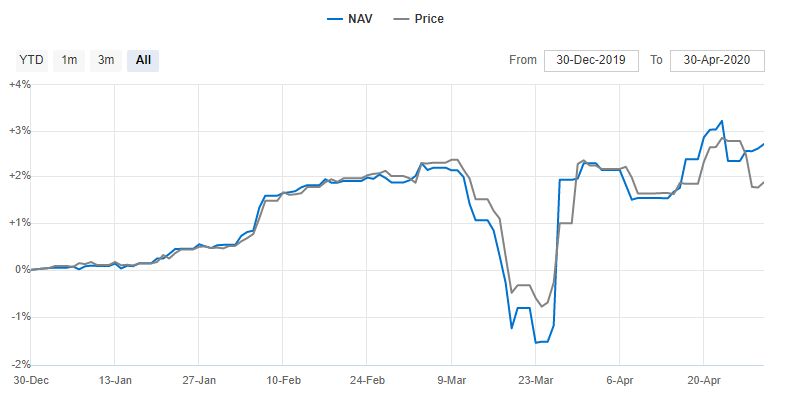

There have been big differences between the price of the ETF and NAV. Here’s the price and NAV chart of the 2023 and 2030 ETFs. Those are big differences, I am not sure if this difference is because of demand and supply, lack of market-making activity or if the market and market makers deciding that the price/NAV isn’t worth arbitraging. But for long term investors, it doesn’t make a whole lot of difference because they can still invest using the fund of fund, which allots units at the end of the day NAV. But anyway, it’s still a really cool product that offers lower credit risk debt exposure at low-cost.

Also, check out this piece by Dave on the drawbacks of NAVs, similar to what I’ve written above.

Incentives

Incentives make the world go around. As Charlie Munger famously said:

Show me the incentives and I will show you the outcome

Charlie Munger

Was Franklin another case of incentives going wrong? What drove Santosh Kamath to assume such risks? Fund manager compensation is linked to the amount of AUM of gather. And to attract assets, you cannot be just another debt fund.

Let’s say if the average returns of a debt category is 7% and you just manage to eke out a 7.2%, it won’t make all that much difference. You won’t wake up in the morning to see that you have Rs 5000 crs of new AUM. To gather AUM, you need to do something special. In debt the only way you can generate high returns is by assuming high risk, that way debt is relatively straightforward to understand compared to equities. Santosh Kamath wasn’t just delivering high returns, he was delivering equity-like returns across most of the debt schemes he was managing.

Pravin in this awesome piece looks at Santosh Kamath’s origins in the industry, his ascent in Franklin, and how it all came undone. But what drove him to assume such risks? Was it just money? A little birdie tells me that he was earning quite HANDSOMELY. At the end of the day, was it just incentives and hubris that were the undoing of Santosh Kamath? Read and find out. I’ll leave you with this telling excerpt from the article:

Kamath’s thought process was similar to that of Michael Milken, the man who created the market for junk bonds for corporate financing and M&A activities. Milken believed that there is always a category of companies ignored by banks, private equity, and even the public markets. These are small companies that require debt and capital, and Milken believed that some of them could grow up to be an Uber or a Tesla. So, lending to such companies was a serious economic activity. In 1990 Milken pleaded guilty for six felony counts and spent two years in jail.

Kamath, like Milken, believed that every time he went after a new company and invested in it, he would be the early bird to bag the highest returns.

ET Prime

Lady liqudidity

A famous Warren Buffett quote goes

You never know who’s swimming naked until the tide goes out

Warren Buffett

I interpret “the tide” as market liquidity. One recurring theme across most market crashes or periods of turbulence is that liquidity dries up which exposes the cracks in products and strategies which otherwise were papered over by bull markets. Even in the case of Franklin, it was liquidity that undid their strategy. If not for the Corona crisis, probably they could’ve pulled this off for a longer time. Which leads to the question – just how liquid is the Indian corporate bond market?

Dhawal Dalal, the fixed income CIO of Edelweiss MF wrote a pretty interesting piece with a lot of data on just how shallow the Indian bond markets are. If you take out G-Secs and AAA-rated bonds, trading volume is almost nonexistent below the AA rung bonds.

This space was Santosh Kamath’s favorite hunting ground. Here are the ratings breakdown of the bonds in the 6 Franklin that are being wound down. It’s a damn risky high-wire act on a triple dose of steroids.

You can now see the reason for Franklin deciding to shut these funds down. In the best of times there’s hardly any trading in AA-rated bonds and below but in a market phase of insane risk aversion, dumping of debt by FIIs, flight to cash, domestic redemptions, not to mention risk aversion in Franklin funds itself post the Vodafone default, these funds didn’t stand a chance. If Franklin had kept these funds open, they’d have had to sell bonds at distressed prices to meet redemptions.

Just for comparison here’s the credit rating breakdown of the SPDR® Bloomberg Barclays High Yield Bond ETF (JNK) and iShares iBoxx $ High Yield Corporate Bond ETF (HYG). Think of these as how credit risk funds in India would be, had our corporate bond markets been larger and deeper. These ETFs are liquidity monsters and except for that brief period in March when every bond ETF and fund had dislocations they trade at a 0.01% spread pretty much all the time.

The post also has data points on the consistent deterioration in the credit quality and balance sheet strength of Indian companies. But what stood out for me in the post was the conclusion. The writer pretty much calls the Indian AMCs inept?

Based on the analysis of the secondary market volumes of A+ rated bonds, deteriorating credit profiles of a section of borrowers, lack of sufficient Cash Flows from Operations to pay for upcoming maturities, current status of credit rating cycle in India, limited ability of AMCs to comprehend legal complexities & protect investor interest in case of a default and mounting pressures to keep honouring redemptions on T+1 basis even in difficult market conditions, I believe that Open-Ended Bond Funds are perhaps not suitable for knowingly taking on credit risk.

Which leads to another question – why are the Indian bond markets so shallow?

Shenanigans

Mutual funds are always up to all sorts of immoral shenanigans that end up with investors getting a golden shaft. Entire books can be written on the shady things they but let’s focus on some of the surprising things that caught people’s attention post-Franklin. Deepak Shenoy wrote a really nice piece on the various types of bonds that mutual funds hold that they have no business holding. The one that stood out for me was that the Franklin Ultra Short Fund was holding a bond maturing in 2029. Remember, Ultra Short funds are supposed to have an average combined duration of less than 6 months.

What Franklin had done was it was holding a floating rate bond. These bonds don’t have a fixed coupon, unlike other bonds. The interest is usually a benchmark rate+spread. And these bonds also have a fixed date during which this rate is reset. So Franklin has considered the reset date as the maturity date for the Macaulay duration calculations. Have to hand it to them, that’s bloody ingenious, but the investors are buggered.

Gotta go deep!

We will deepen the Indian bond markets is to the capital markets what we will provide jobs, 24 hours power, water, good roads, education is to politics. Countless committees have constituted, tonnes of reports have been published, yet the Indian bond markets remain as shallow as an episode of Keeping Up with the Kardashians.

Why?

Rajiv in part of 2 of the series tackles this question:

Many initiatives taken over the years to increase participation in the debt market languished and were ultimately forgotten. One of the primary reasons for these failures has been the inability of the RBI and Sebi to jointly work towards making the necessary changes to this market.

ET Prime

Think about it, mutual funds are regulated by SEBI while most debt securities except for corporate bonds are regulated by the RBI, kinda weird, isn’t it? To make things more complicated SEBI regulates rating agencies which rate money market instruments etc which are under the purview of the RBI. We all know just how amazingly, selflessly, different regulatory bodies set aside their agendas and egos and work together for the betterment of the Indian capital markets ecosystem 🤦

Not just that, difficulties in foreigners investing in debt, tax arbitrage between mutual funds and other structures like AIFs, and between mutual funds and directly buying bonds etc are a few more reasons why bond markets have remained in a state of stasis.

And even when it comes to investors, bonds aren’t really all that popular because there’s no bloody liquidity in listed bonds on the exchanges. Which is one of the reasons why FDs are so popular. Up until last year, there was no easy way for retail investors to buy G-Secs and T-bills. Finally, the RBI opened up a non-competitive bidding mechanism trough the exchanges to make this easier. As for corporate bonds, retail investors have to rely on banks, bond dealers, etc where there’s no standardized pricing and buy them through off-market transfers. The only easy way to access fixed income instruments is through mutual funds.

What to do?

Whenever there’s a crisis, investors freak out and resort to doing really horribly stupid things. Like redeeming liquid funds and putting that money in a gilt fund – YES, I’ve received this query a couple of times. Picking a debt fund can be hard for most retail investors. So, what do you do?

The most common thumb rules people follow when it comes to debt funds are:

- Invest in the funds with the highest AUM

- Stick to funds with only AAA-rated bonds

- If you don’t know what category to pick, choose a liquid fund or a banking & PSU fund

Not that that, these are bad thumb rules, but they aren’t foolproof as recent events have shown us. Franklin Ultra Short Fund was one of the biggest funds in the category and now it’s being shut down. IL&FS and DHFL were AAA-rated until they went bust. Banking & PSU funds can invest 20% of their portfolio in non-banking and non-PSU bonds. Not just this, liquidity as it turns out, is as big of a worry as poor credit quality. So, if you are wondering, what the hell you should do, check out this really good Primeinvestor piece which has some really good tips on choosing debt funds.

One takeaway for me from this article, I always through diversifying across AMCs was a silly thing to do. I’ll admit, I was bloody wrong, not that anything is wrong with my portfolio. But the Franklin episode has shown that when it comes to debt having all your eggs in a single basket is a terrible idea.

What’s in a name?

Aarati Krishnan wrote a really interesting piece on the lessons from the Franklin disaster. A couple of really important passages from the piece the piece worth highlighting:

Bala: I also think mixing up retail investors, HNIs and corporate treasuries in the same fund is like asking lambs to live with wolves. Debt funds for retail investors must be separate.

This is a really interesting idea. If a fund is popular and used by corporate treasuries, and if the fund has issues, the corporate money will flee overnight. This means the fund has to sell all the liquid assets to meet the redemptions and by the time the selling is done, chances are the fund will be left with relatively less liquid stuff. This means that the small investors will be left holding the bag and exiting the fund if they want to becomes difficult. When there’s a serious flight of money, it also leads to concentration issues in funds because the existing holdings will continue to grow as a % of the total assets as liquid bonds are sold.

Another important point raised in the piece on product labelling.

Srividya: I would also argue for AMCs calling a spade a spade in naming their products and not using euphemisms like ‘accrual’ or ‘high yield’. With innocent names like Short Term Income Plan, Low Duration Fund or Income Opportunities, how would lay investors know the risks? Advisors may have known what went on in FT schemes, but did your father know, Bala?

And this risk-o-meter is so wishy-washy. How can credit risk funds and corporate bond funds both be ‘moderate’ risk?

This is something I’ve been raving and ranting like a lunatic, especially in the hybrid space. Which genius came up with Blanaced Hybrid and Balanced Advantage? And not to mention the idiocy the product labels. Ironically, even though these riskometers are tucked away in some corners of AMC websites and platforms, surprisingly people consider the risk label in their decision making, much to my shock.

If so many people seem enticed by the returns of credit risk funds in spite of having the word “risk” in the name, imagine how many more unwitting investors would’ve been smitten if the category was labeled as “credit opportunities” instead.

Unfortunately, investors are smitten by labels, they shouldn’t be, but they are.

Speaking of credit risk funds, I’ve been having a lot of debates with fans of this category. I think this is an utterly, totally, completely useless category. Now bear in mind, I readily admit I have a lower single-digit IQ and a bottle of Colin is way smarter than to me. But in spite of my mental deficiencies, credit risk funds seem like corporate bond funds with higher default risk, higher expense ratios, and lower returns.

Here’s a quick comparison of Credit risk funds with 1000 cr+ in AUM. I don’t get the point of talking all that extra risk in AA rated papers and below just for a 0.5% to 1% extra return. I’d rather stick to a decent corporate bond fund given the choice between a credit risk fund.

Having said that, the only time investing in a credit risk fund ironically makes sense is if someone is running a strategy similar to Franklin. Say what you want about Santosh Kamath, the man ran a proper high yield fund. 50% of the AUM in A-rated papers and below, that’s the real credit risk investing.

Fallout

The fallout from the Franklin fiasco is that for the time being, debt fund investors are worried and rightfully so. But I’m an eternal optimist in my belief that a good chunk of these investors will go back to doing the same thing over and over again.

At the industry level, Credit Risk funds are bleeding assets and rightfully so. These damn funds should’ve never been accessible to retail investors in the first place. But, once the markets calm down, I’m sure, they’ll be hawked like vegetables and investors will chase returns again. And so continue the endless cycle of retail investors doing dumb things over and over again.

There was a sharper fall in some of the remaining Franklin India debt schemes too

Damn, this post got big.